Prince and the Tech Revolution

Photography by Toby Shaw

A childhood passion for fixing things led Prince Tino to build a business that’s helped tens of thousands of South African children become computer literate. Now living in Hastings, he says his mission is far from finished.

In 2019, South Africa’s SABC News posted a video clip to its 2.8m YouTube subscribers. In it a 10-year-old boy, Phodzo Nemutanzhela, sits in the studio dressed in a suit and tie, chatting to the news anchor about computing. He says he can now assemble a computer without any help, and reels off a list of components with such fluency it leaves the presenter Desiree Chauke momentarily speechless. “I’m bowled over,” she says. “Tears in my eyes, I’m sorry.”

In a country plagued by skills shortages in key areas such as IT and healthcare, this young boy represented new possibility.

But his technical know-how didn’t come from a national educational initiative; it was down to the vision of one man. And today he is sitting upstairs in Folks coffee shop in St Leonards, telling his story between sips of hot chocolate. Now 39, Prince Tino has always had a passion for fixing things – whether that be computers, people or wider social issues. He moved to the UK from Johannesburg, South Africa two years ago to work as a health care worker, and from his base in Hastings he continues to remotely run the company that’s still changing young lives back in South Africa.

It was an idea that came to Prince when he was 26 and working both as a waiter and computer repair guy in Johannesburg. “It’s about making the next generation computer literate,” says Prince. “Everything now revolves around computers, so we need to prepare these kids. I thought, ‘OK, I’ve got IT knowledge that it’s not possible for a lot of communities in South Africa to access.’ A lot of kids don’t use a computer until later in life – of course it’s the most underprivileged who suffer most. The country is falling behind. I didn’t see anyone who was willing to [help fix] it, so I came up with a way to impart my knowledge.”

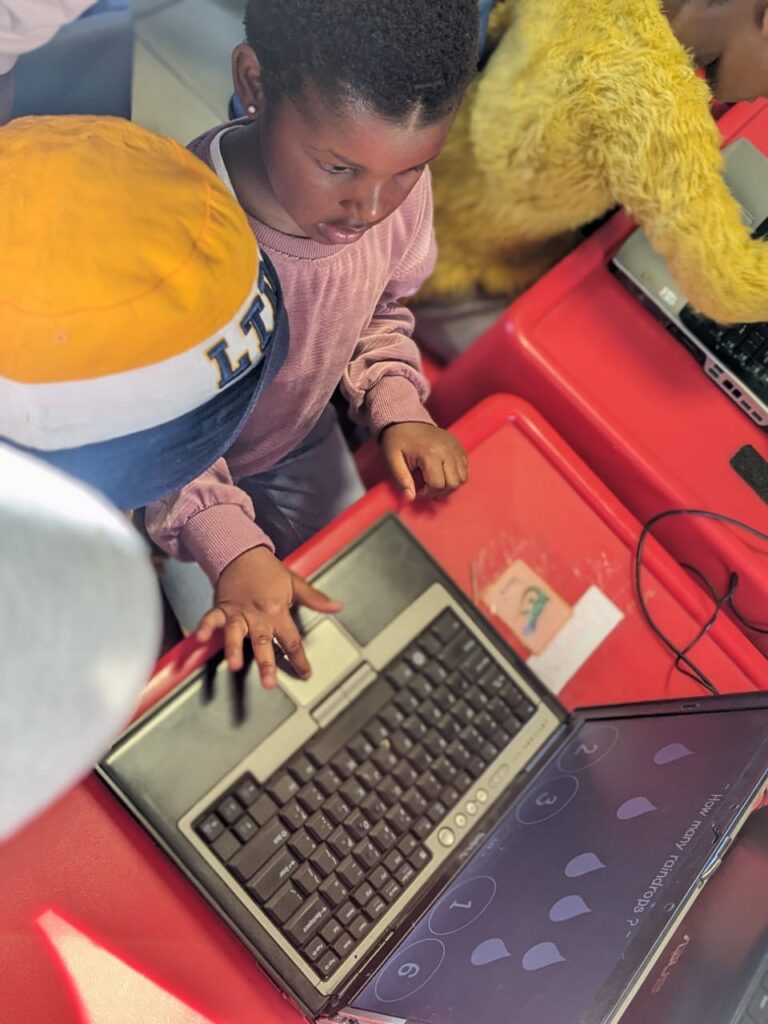

In 2012 Prince founded the Tino Tech Funda Youth Project offering computer-based lessons in South African townships where kids needed them most. Starting out completely alone, he’s now grown it into a substantial non-profit organisation operating across Johannesburg, employing 15 full-time teachers to work with kids from the age of two up to 12. To date, they’ve taught more than 20,000 children.

“There’s a lot of work that still needs to be done,” says Prince, “and if I don’t do it, probably somebody else is not going to think about it. So that’s what keeps me going. That’s what drives me.”

The strength of Prince’s drive is clear from the sheer amount he achieves. Aside from Tino Tech, and his health care work, for years he’s also put on music events and festivals that usually focus on new, unsung or unknown artists. Everything he does has community at its heart, something he says he got from his parents.

“My mother, my father, they were always people who always liked to give back to the community,” he says. “My mother was a nurse for 20 years. She always used to say, ‘Help the next person. You never know, how much it’s gonna change their lives’. So that was just passed on. That’s how I got to love caring for other people, for putting other people first.” of the skills and beliefs he’s built over decades.

Prince comes from a township in Bulawayo, Southern Africa , and was the second of four children born into a family of musicians. “My dad was a guitar player and a singer,” he says. “My mother was a singer too, and used to play tambourine. So in the house, we always had instruments – a piano, guitars. Literally, there was no escape for any one of us.” He laughs at the memory. As a result Prince is now a skilled guitar player himself, but it was a screwdriver he picked up first.

“I was always a child who always wanted to fix things,” says Prince. “I always wanted to open up a radio and see what’s inside, see what’s wrong with it. That’s how I got the love for gadgets – radios, VCRs, anything I could find.”

Realising this was more than just a phase, Prince’s mother enrolled him in technical college when he was 14. “Eventually I started learning how to put computers together, getting this part, that part. It was freedom. I loved it – it was what I always wanted. Then as I grew older, I started buying parts, building computers. I didn’t have much access to things like YouTube back then, so I read books. Technical stuff, but also about Bill Gates, how he managed to do what he did.”

When he turned 18, Prince moved to Johannesburg to start a new life, and learned first-hand the value of IT skills as he tried to establish himself. “I never wanted to ask for money, I wanted to make money myself,” says Prince. “[My computer skills] weren’t even that good at that time, but I’d go around Johannesburg to different places and handout flyers advertising my services. If I ever got stuck [on a job], I’d go to a professional and be like, ‘Please help me.’ They were good enough to teach me. They were patient enough to help.”

With his business growing and other jobs such as waiting tables supplementing his income, Prince saved up enough to buy a car to help him transport all the hardware he was fixing. It was a red Mazda 323. “It was old, but it was mine! I was so proud of that car,” he grins. “But after a while I felt I was stuck. I’ve always had this thing of not wanting to be comfortable, I always want to see what else can I do, to push myself. I knew I hadn’t reached my limit. Then I came up with this idea of imparting my knowledge to the kids.”

Rather than targeting primary or secondary school-age kids, Prince felt certain it would be better to start as early as possible, with two- and three-year-old children at nurseries and preschools. “I was really sure young kids can absorb anything you give them,” he says. “So we need to fully equip them at a young age.”

With no prior teaching experience and no funding, Prince drew up a proposal of the sorts of lessons he thought would work and began to visit nurseries and creches to sell them on his unusual idea. “I went to talk to the to the principals, the managers,” he says. “Most said, ‘We don’t think it’s gonna work’ or some would say, ‘Maybe later, we’ll see’. But then one of the preschools said they would give it a go.”

Armed with his knowledge and not a lot else, now Prince had to work out how to get hold of the equipment he needed to teach his lessons. His pride and joy, the Mazda, was sacrificed. “I knew if wanted to start this, I’m gonna have to take risks,” he says. “So I sold my car and bought a few computers.”

Without his own transport, on his first day in business Prince found himself walking back and forth along a mile-long highway on foot, carrying each of the three desktop computers he needed for the lesson one at a time in his arms, from his home to the nursery. “It wasn’t easy,” he says, “but that’s one thing that I told myself, I want to feel that pain. This is what I wanted to do.”

He didn’t even end up using the computers at the introductory lesson. “Instead I created a story about how computers started,” he says. “I told them about [‘father of the computer’] Charles Babbage from England. I tried to paint a picture to get the kids curious, how big the first computer he designed was, I described this huge machine. I was so motivated after the lesson – I wasn’t really expecting the kids to be so positive about it. Then the next day, parents were ringing like, ‘Wow, my kid’s talking about Mr. Charles Babbage, who’s that? What’s happening?’ With every lesson I picked up new things, saw what was working and what wasn’t. I was learning a lot.”

Prince says that each year since then, Tino Tech has roughly doubled in size as more nurseries and then schools signed up. Prince was charging around £1.50 per child, per month to attend weekly classes, to keep them accessible while just about covering his operational costs. As the business grew, Tino Tech employed teachers, and developed teaching programmes for older children too. A big part of the approach is using computer software to improve children’s maths and literacy skills with games and puzzles. But they also learn how to recognise and assemble the hardware, giving primary school-age kids a better practical knowledge of computers than most adults gain in a lifetime.

“This year we are introducing lessons in robotics for the kids,” Prince says, “and soon we’ll start teaching the programming side of things. There’s so much still to do.”

In person, Prince is warm and softly spoken, a smile rarely leaving his face as he recounts his many and varied experiences. His passion for Tino Tech and the children it helps is obvious (“I get emotional when I see what these kids can achieve”) making his decision to relocate to Hastings eight thousand miles away from Johannesburg to work in the care sector hard to fathom at first. But the move was motivated by exactly the same urge to help that led him to found Tino Tech.

Prince was already volunteering at care homes for the elderly in his spare time when COVID struck. When he saw how inadequate the national response was to the crisis, he did some training in sanitisation and assembled a team of people to help out as a voluntary service.

“It was overwhelming the health system,” he says. “It took everybody by surprise. So we’d get calls from the health department to say please go and disinfect these places. At one point I remember we had to start counselling people, because some were getting traumatized. It was hectic. When the cases started to reduce, that’s when I decided I would love to take up care work, again it has to do with community. So I did some college studies, and started looking for jobs that would be different, challenging. I saw a role in Hastings, applied for it, and here I am.”

Prince still visits South Africa fairly regularly. In a few weeks he’s putting on a festival in Johannesburg he’s been organising remotely with a team on the ground in South Africa. The theme is on-brand for Prince. “It’s a community project celebrating unknown artists,” he says. “The great musicians behind the big names who don’t get recognised.”

And he’s brimming with other ideas. He wants to take a band from the UK to play his festival next year and, having stage-managed last year’s Hidden Beach festival at The Oval, he would love to organise his own festival here. He also dreams of offering children and their parents in Hastings and St Leonards workshops on computer literacy. And he’s already unofficially helping the elderly clients he cares for with their IT skills. “Some of them struggle with technology,” he says. “I find myself giving them lessons, making them aware of cyber bullying, cyber security. I know it’s not part of my job description, but the little I can do is just to make them aware. We need to educate the elderly too.”

And of course he’s still focussed on growing Tino Tech. He’s always looking for donations of working desktop computers, laptops or tablets to further the cause. “One thing that really drives the whole project is the equipment,” he says. “The more equipment you have, the more communities you can reach.”

Prince is consistently modest about his achievements, but it’s clear he’s had to take brave risks to do what he has – putting everything he owned on the line, moving himself and his supportive partner to a new continent. “It’s worked out for me,” he says. “I see these things happening in my life and ask myself, ‘How did I get this?’ Then I realise, maybe it’s because of the good work that I’m doing. I won’t change; I’ve always been a simple person, I’m always gonna be a simple person. I have to work with the community, I have to help people. That’s how my life has always been and that’s how my life will always be.”

With that, Prince drains his mug, looks at the time and apologetically announces he has to leave. He has work to do.

If you have any working computer equipment you could donate to Tino Tech, contact Prince at tinotech2012@gmail.com.

*